Childhood Trauma: Losing My Father

My dad loved basketball. Throughout my childhood, he was a member of our church league. He played frequently and took it pretty seriously—and was really good. Toward the end of 1997 while playing an evening game near our home, he suffered an injury and required subsequent surgery to repair his Achilles tendon. After his surgery, he wore a bright blue cast that extended up to his knee. He was required to use crutches, unable to bear any weight on his injured leg.

The following January, my dad’s organization hosted a conference in Jackson for college administrators, professors, and students. More than 300 attendees assembled in a downtown hotel to listen to speakers, attend workshops, and discuss with colleagues all the aspects of race and ethnicity encountered on a college campus.

I was excited for this particular conference: since it was in our hometown, I knew I would be allowed to skip school and tag along and watch my dad speak. I remember my dad’s frustration with his cast and crutches. During the morning portion of the conference, he made his way slowly around the facility but spent a good amount of time camped out at the book table, selling copies of More than Equals, speaking with students and answering questions.

At one point, he called me over and told me he wasn’t feeling well. A diabetic, he suspected his blood sugar was low, so he sent me to a vending machine to purchase juice for him, with the hopes that it would level him out. After completing my errand, I scampered off to explore.

I remember participating in the breakout session portion of the program later that afternoon. I chose the breakout group on the topic of multiculturalism, specifically existing as a biracial person. (Yes, I’ve been interested in race and racism since childhood.)

I don’t remember well the substance of the session, but I do remember the overwhelming feeling of comfort I experienced. I had not met many other biracial individuals at that point in my 11-year-old life and participating in a discussion in a room surrounded by people with similar racial backgrounds was fun. After the breakout sessions, all of the conference attendees reconvened in the main auditorium. One by one, the various breakout group leaders recapped their respective meeting highlights with the entire conference.

When the biracial breakout group leader began her recap, she asked all of the attendees to stand. I remember being a bit nervous as I stood there, but also beaming with pride at my participation in something so grown-up. I felt like one of the adults, and I knew my dad was proud that I had participated.

Just as we were about to sit down, I was bombarded with what I can honestly say was, and still is, the most horrifying sound I have ever heard.

It was a scream.

Recalling the scream gives me chills even today as I write this. It rang out across the conference auditorium, piercing our eardrums, traveling up and down the isles, bouncing off the ceiling, and surrounding each of us, all at once. I identified the voice in the split second it took for the sound to hit my ears, just as I spun around toward it: my mom. She was standing above my seated father, cradling his head in both of her hands and hugging him at the same time.

Help! Something’s wrong with Spencer!

The room erupted, the attendees scrambling, knocking over chairs to get to my dad’s side.

My dad was unconscious. I remember being yanked from my aisle and rushed toward my parents. My dad was appearing to regain consciousness. I heard someone yell, “He’s asking for Johnathan! Where’s Johnathan!?”

Within seconds, I was plopped right in front of my dad. I remember him making direct eye contact with me, his eyes glassy and somewhat glazed over. I was terrified. Something was seriously wrong with my dad. I heard someone exclaim, “See, Spencer, Johnathan’s fine. He’s right here!” The rest of the scene is a bit of a blur. I remember someone calling 911 and multiple conference attendees (perhaps doctors) caring for my dad. I was placed into a car with family friends, and whisked away to the hospital.

We actually arrived at the hospital before my dad’s ambulance did. By the time it pulled into the emergency department port, my dad was conscious, speaking to my mom almost casually it seemed. I remember looking through the ambulance window and seeing my dad interact with the paramedic treating him. He seemed to be totally fine.

Once inside, we were reunited; my father was kept for observation for a short while and then discharged. From what I recall, the consensus was that he had fainted, likely due to low blood sugar, dehydration, exhaustion, or all three. He had been particularly stressed leading up to the conference, because of publication deadlines and because he was on crutches, not able to be as mobile as normal and thus, not able to contribute as much as he would have liked.

When we arrived home from the hospital, one of my dad’s main concerns was, of course, whether he would be able to give a speech scheduled for the following evening at a local college. He was fairly adamant that he was all right and he would just take it easy and give the speech.

Sure enough, the next evening my dad and his co-author Chris gave a speech at Belhaven University. I was excited to attend this event as well. Usually, my dad and Chris gave most of their talks at various conferences or universities around the country, so I was thrilled to once again be able to attend and watch my dad.

I was cautious, though. Something was not right about my dad. He hadn’t been right all day. As I watched him speak, seated next to a standing Chris at the lectern, I remember noticing that my dad was short of breath. He was also sweating fairly-profusely. I’d imagine that many attendees (who had never before heard him speak) probably chalked this up to nerves. I’m sure many didn’t even notice. I did.

My dad and Chris finished up their speech without incident and we went home. That night, my dad, still short of breath at times, assured us that he had scheduled a chest x-ray for the following day. Satisfied that the x-ray might provide us with an answer to his odd symptoms, we ate dinner, relaxed.

My dad, resting in bed, called me into his room on my way to my bedroom. He told me goodnight and I headed to my bedroom for the night.

I had school the next day. Aside from the normal social issues that haunt any preteen, my last semester of sixth grade at Peeples Middle School was going well. I don’t remember much about the school day because it was so unremarkable. Normal day, normal interactions, normal everything. Nothing was out of the ordinary until I was waiting with my friends for our ride home to arrive.

We were all surprised to see Tressa Eide pull up at our waiting spot. Tressa’s son Erik was (and still is) my best friend. Erik and I were born only months apart, had grown up together, and had spent just about every weekend together at one of our houses. Erik was always welcome at our home, and I felt the same from the Eides. Tressa had become a second-mother figure to me throughout the years and I was happy to see that she, as opposed to our usual ride, was picking us up from school.

When we got into the car, Tressa told us that there was a bit of a change of plans: “We’re going to be dropping Johnathan off at the hospital.” More welcomed news. I knew my dad was going to the hospital for his chest x-ray and I was eager to tell him about my day. I remember gabbing on to Tressa about whatever had happened to me at school that day, the whole way to the hospital.

Looking back, I now recall that Tressa was not her usual self during that car ride. She was normally quite talkative, high-spirited, and animated. But during that ride, she was soft-spoken, never even turning to look at me as she spoke. I didn’t think much of it at the time.

When we arrived at the hospital parking lot, I noticed a few familiar cars—people from church. Maybe they were here to visit my dad, too? I didn’t think much of that either. We exited Tressa’s car and she escorted us inside. Once inside, I realized that there were a lot more people I recognized than I had anticipated. We waded through what were probably ten or fifteen people, presumably all there to visit my dad. None of them uttered a word to me—some did not even look at me.

This was weird. Something was wrong.

We continued, winding through the twisting hallways. Two or three people from the community had joined our group as we passed by them. Along the way, I saw a couple of people mouth the words, where’s Nancy? When we finally arrived at the proper room, Tressa opened the door and I walked inside. I recognized everyone inside the room, including my grandfather (my dad’s dad) and my dad’s co-author and friend Chris.

My mom was seated in the middle of the tiny room. She had been crying. Her face was bright red and she was leaning forward in her chair with her elbows on her knees. She reached her arms out to me, inviting me for a hug. She hugged me hard, beginning to cry again. When we pulled away from each other, she held both of my shoulders tightly and whispered through tears, “he’s gone—we lost dad.”

Earlier that day, while my mom was out of the house, my father had experienced what we later learned was a sudden, massive heart attack. He had been seated in his favorite chair and, as the heart attack began, he had telephoned my aunt who was next door for help. She heard him whisper “I can’t breathe” over the phone. She and my uncle ran to my dad’s aid.

Once inside our house, my aunt tells me that they believed my dad was experiencing another diabetic episode similar to the one he had at the conference a few days earlier. She describes her and her husband calling 911 and then running around the house in a panic, in search for something to feed to my father to elevate his blood sugar.

We now know that nothing my aunt and uncle could’ve given my father would have saved him. In fact, we later learned that there was nothing they could have done to aid him at all. The heart attack was simply too massive.

My dad was unresponsive by the time the paramedics arrived.

Back at the hospital, inside of the tiny room, my mom tried to comfort me: “They did everything they could. They tried really hard for a long time. He’s so young!”

My sisters Jubilee and April arrived shortly thereafter, and I watched my mom convey the same news to Jubilee. I remember her clutching my youngest sister April in her arms. “She’s only four! She doesn’t even understand what’s happening!”

It was important to some people—I’m not sure who—that we see my dad’s body. I suspect people thought that this type of real life confrontation was important for the grieving process. Probably part religious and part superstitious.

I remember exiting the small room, my mom carrying April and clutching Jubilee and me tightly to her own body. Someone said “he’s in here.” The room we entered was eerily sterile, steel everything, with a table situated at its center.

It was like a scene from a movie. A long object was displayed on the table under a white sheet. I remember thinking to myself, this is just like a movie; this isn’t real. With very little warning, one of the doctors pulled back the sheet to reveal my dad’s body lying there, his face, head, shoulders, and upper chest exposed to the cold room. His skin had a grayish hue to it. His eyes were partially open.

I remember my grandfather gripping my left shoulder tightly and saying, “you need to go kiss your dad and say goodbye.” Was he serious? Was this real? I felt my heart pounding in my chest. I stared at my dad, expecting him to open his eyes and sit up. Eventually, I did as I was told. Terrified and horrified, I kissed my dad on the forehead, said goodbye, and quickly backed away.

The next few days are a bit of a blur. Upon hearing the news, my mom’s parents and a few of my aunts and uncles on my mom’s side drove immediately from their homes in Pennsylvania to be with us in Mississippi. Our house was flooded with friends and family. Church and community members flowed in and out of our home, bringing food, flowers, and anything else we needed.

I remember my best friend Erik most of all. We spent hours in my room together, just talking, reminiscing about my dad, crying. I cried so much over the next few days. The tears would overcome me when someone would remind me of my father—or when nothing did.

My sadness was unpredictable, and all-consuming. My father traveled a lot so, to me, his physical absence wasn’t particularly striking. In my mind, he would be coming home in a couple of days, like he always did. I had to continue to remind myself that, this time, this was not the case.

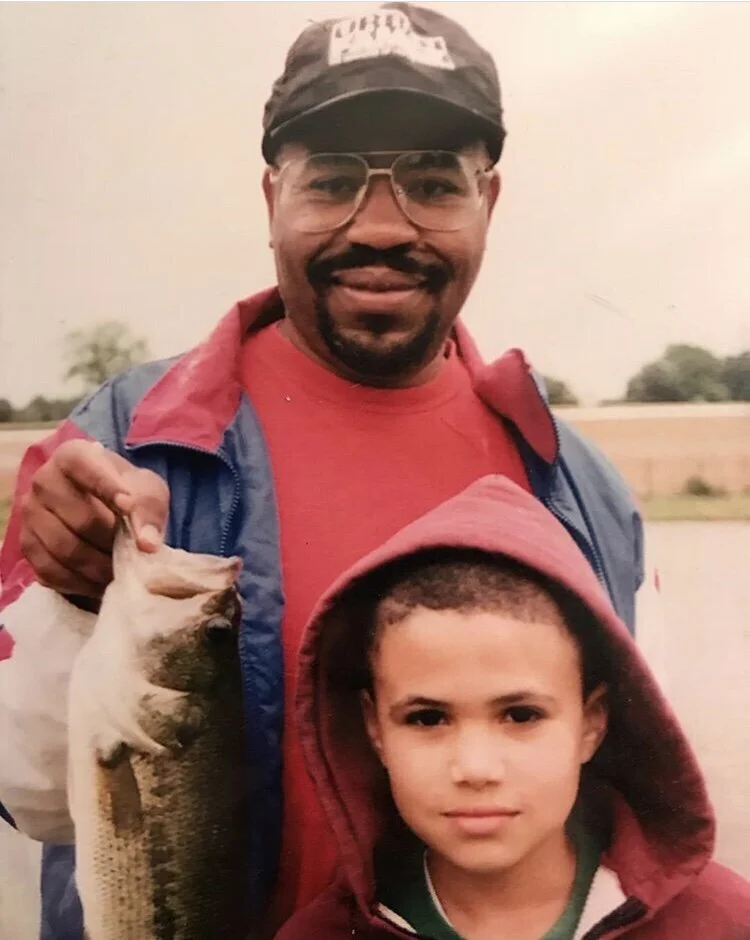

I had to make the bizarre adjustment of referring to my dad in the past tense. I had to remind myself that I would literally never talk to him again. I would never hear his voice. We would never laugh together. He would never sneak into my bedroom at the crack of dawn and whisper, “let’s play hooky today and go fishing.” On this Earth, I would never have a father again.

I can’t express enough how masterfully my mom handled and continues to handle the cards she has been dealt. She grieved—we all did—but she never took her eye off of the ball. In the midst of the most traumatic period of her life, she never forgot that she was our mother and that my sisters and I were her first priority.

She told us that.

Every decision she made, throughout the immediate grieving processes, as well as in the months and years that followed, was made with our best interests at the forefront. Her most dramatic decision was to move our family from Mississippi to Pennsylvania, to be closer to my mom’s family. She knew that the move would be a tough adjustment for all of us, but she knew it would also be what was ultimately best for us.

My mom prioritized my sisters and me in a way that’s hard for me to adequately explain. She looked into the future and predicted our troubles, our needs, and our questions. She positioned us in a way that gave us the best possible chance of adjusting to the loss of our father in the least harmful way. She shielded us but at the same time allowed us to experience and process our grief.

I remember an instance, perhaps only a few hours after my dad had died, where she took me aside, sat me down, and explained one of the most important concepts that would follow me and comfort me throughout my entire life:

People will tell you that you will need to step up and be the man of the house now that dad’s gone. Don’t listen to them. You do not need to try to take care of us. You do not need to try to be the dad. You are my child and I am your mother. That will never change. You are my child. It’s my job to take care of you—not the other way around.

These instructions governed my entire life. They still do. They relieved a sense of pressure that, at the time, I did not even know I would have. I love my mom so much for this. She was wise in a way that I didn’t know people could be.

We all processed the loss of my dad differently, but together. I don’t think you can ever fully process the loss of a parent. It’s not something you get over. It’s not something you ever fully come to terms with.

Over the years, my mom taught me that closure—the way I had heard many people talk about it—is a myth. It doesn’t exist. Her lessons allowed me to come to terms with the fact that sadness is a part of my life, a part of all of our lives—and that’s all right. It’s for that reason that there’s no clever or even convenient way to end this recollection.

There’s no neat bow to put on this. No lesson learned. No moral resolution. I only hope that I am making my dad proud. That hope is part of what drives me.

And I’d like to think that I am.