What White Allyship Looks Like: An Open Letter

Dear White Allies:

Much of what I have written on the topic of race and racism may have left you feeling hopeless and defeated, with no action items, no way to overcome the racism inherent to your whiteness, no clear way forward. This letter is meant to offer my perspective on that way forward—and offer advice on how you can play a key role in the movement toward racial equity.

First, a Preface

Before we delve into what true allyship looks like, it’s important to get this out of the way:

It is not my (nor any black person’s) obligation or responsibility to give input or advice on race, racism, or allyship. Black people have no obligation to assist white people in their anti-racism efforts, as the oppressed have no moral obligation to educate and advise the oppressor on how to best end that oppression. Any advice or input black people choose to give you with respect to your anti-racism efforts should be viewed as just that, our choice—not an expectation or requirement. It’s safe to say that you probably shouldn’t even ask black people for such advice unless they (like me) have made it clear that they’re open to sharing their perspective. If you’d like to strengthen and refine your allyship but need guidance, remember that plenty has been written on this subject and resources abound, many of which are provided and maintained by other white people.

Finally, if your reaction to the substance of this letter is defensiveness or anger, I’d direct you to what I and others have written on the role that white feelings and white fragility play in dialogues about race. While my words may be perceived as aggressive or glib, rest assured, they have been chosen deliberately and come from a place of frustration, anger, and pain.

This letter is meant to serve as a resource for allies strictly for purposes of your individualized, interpersonal interactions—more to come on carrying out anti-racism work on an institutional level. Because this letter is meant for white allies who already consider themselves effective and/or know they can do more, I presume a baseline degree of racial competence, informed, in part, by your preexisting intimate (not necessarily romantic) relationships with black and brown people. Your intimate relationships with black people should serve as regular insight into the true harms of racism. If you do not have deep, personal relationships with black people, ask yourself why before you continue to implement anti-racism work that is aimed at others.

What effective White Allyship Looks Like

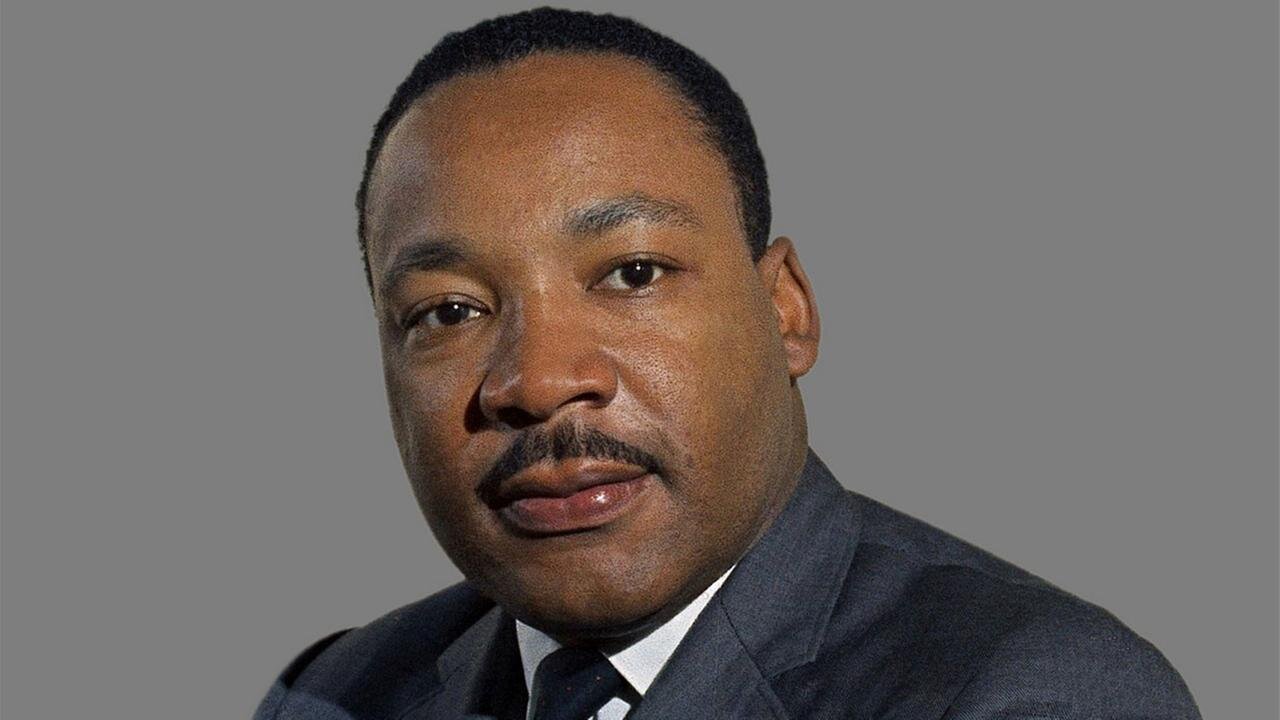

On this day, dedicated to the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., it’s incumbent upon us, in our exploration of white allyship, to examine Dr. King’s stance on the role of well-meaning white people. In his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Dr. King writes:

“First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro's great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen's Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice . . . .”

In guarding against what Dr. King believed was racial equality’s greatest obstacle—complacent white people, fearful of disturbing social norms—true racial allies must be disruptive. They must intentionally upend those norms. What’s more, they must not be content with the status quo nor afraid of the backlash they might personally suffer as a result of calling out even the slightest expressions of whiteness as the norm, or worse, as supreme.

White allies have a vital role to play in bringing about true racial equality. The actions white allies must carry out, if racial equality is ever to be attained, are difficult to execute consistently. But I am confident that, with time and persistence, truly effective allies can grow their numbers and, more importantly, their impact, and perform the work necessary to ensure true racial equity.

It’s Who You Are — And It’ll Get Uncomfortable

From a practical day-to-day perspective, a commitment to constant intensity is vital. Because of the expansive and systemic nature of American racism, anti-racism efforts cannot be treated as simply another “cause” you champion. An ally must be who you are, not simply a thing you sometimes do. If you are truly committed to racial allyship, real changes to your everyday life including vocalization of your anti-racism work (not seeking gratitude, but as a way to educate other white people) is a requirement. As an ally, you must speak out publicly against every expression of whiteness you observe: every benefit society offers you or other white people and every instance in which you observe whiteness covertly or overtly harming non-whites. And you must commit to this practice for the rest of your life—no exceptions.

You must become the person who “always makes everything about race.” I assure you, once you start paying close attention, you’ll begin to realize (if you haven’t already) that, when examined critically, most things are informed by race in one way or another. In becoming known as the white person who always talks about race, your reputation for discussing race issues should precede you to such an extent that those with whom you interact monitor themselves to make certain that they don’t express even the slightest racially-charged micro-aggression in your presence. (Imagine what race relations in the U.S. will look like as those who share your reputation begin to grow in number and eventually outnumber those who do not.)

In order to expand and maximize your anti-racism efforts, you must publicize your allyship as well as your commitment to becoming a source of knowledge on race issues for other white people (in a way that does not seek gratitude or recognition). You must carry out these public functions of your allyship while also remembering to appreciate, accept, and defer to the opinions and perspectives of the black and brown people in your life.

From an emotional and psychological perspective, one of the most important things to bear in mind as you proceed as an effective racial ally is that true allyship, by definition, will cause what will feel like self-inflicted harm. Actively working to remove yourself and other white people from a position of societal supremacy will be inherently jarring and uncomfortable. It will feel like punishment or even self-imposed discrimination against you, as a member of the very racial group whose power and supremacy you’re attempting to challenge.

Don’t ignore that discomfort. Pay attention to it. Take account of it. It’ll be one of the most accurate (and one of the only) measures of your progress. If your allyship efforts don’t cause personal negative consequences, then you’re not trying hard enough. The expansive role white supremacy plays in this country’s society dictates that white people will experience what will feel like negative repercussions as a result of dismantling that role.

Everyday Ways to Combat White Supremacy

In the context of my own anti-racism efforts, which often involve engaging white allies or would-be allies and providing advice and perspective, I’ve noticed that they often ask for specific examples of interpersonal instances where they might step up and speak out. My most succinct answer is: whenever and wherever you detect that race is informing an interaction.

Since I hope to convey as much context and applicability as possible, I’ve put together a (non-exhaustive) list of hypothetical interpersonal examples that come to mind:

Question your supervisor when you suspect your black colleague’s work is being scrutinized more closely than yours.

Press your supervisor for the specific reasons you received a promotion instead of your black colleague whom you believe deserved it more than you.

Ask your co-worker to clarify what he means when he says things like, “Tyler is weird to work with. I just don’t have the same vibe with him as I do with my other co-workers.”

Call out your co-worker when he says things like, “I was surprised when I saw that the new guy was black. Tyler doesn’t seem like a black name.”

Ask your company’s human resources department about racial minority recruiting efforts and affirmative action policies. Follow up.

Ask your white friends why they call certain neighborhoods “up-and-coming” and whether they have ever thought about the implications of such a term.

Demand an explanation from retail clerks when you observe them closely following and monitoring black patrons.

Educate your friends as to why the use of “ghetto” as a pejorative adjective (as in, “some of the keys are missing from my ghetto laptop keyboard”) is inappropriate.

Call out your white friends when they say things like, “I sometimes forget she’s black because she talks so white,” or “Michelle is the whitest black person I’ve ever met, ” or “David isn’t like a normal black person,” or “David, that was so white of you.”

Educate your friends on why reverse-racism isn’t a real thing.

Demand an explanation from your white friends when they say things like, “she’s pretty for a black girl.”

Explain why it’s not a compliment to tell a black person things like, “you’re a credit to your race,” or “you’re so articulate.”

In order to maximize your effectiveness as a racial ally, you will have to execute small corrections like these as often as possible—even, or perhaps especially when, black and brown people aren’t around. Hopefully, you’ll get to a point where you don’t have to, but where you want to, where you feel compelled to. Remember, at times, perhaps more often than not, speaking out will be considered socially unacceptable. It will be awkward. There will be consequences. Social, professional, familial, and otherwise.

As you develop your reputation as someone who monitors other white people, seemingly-obsessed with detecting, identifying, and calling out racially-informed exchanges, micro-aggressions or otherwise, other white people will undoubtedly consider you someone who hates and attacks their own race. You’ll know you’re doing this right if your non-ally white friends begin to find you socially odd and unappealing. Moreover, you should ultimately make the deliberate decision to refuse to associate with other white people who—after reasonable attempts at education—choose not to share your commitment to allyship. You must also publicize the reason for your refusal to associate.

In Conclusion: You Can Do This

Again, fighting to dismantle white supremacy is not merely a “cause” to be supported at one’s leisure. White supremacy is too deeply embedded in America’s social fabric to be effectively eradicated by utilizing anything other than extreme and constant means.

Destroying white supremacy’s role within the U.S. will require a dramatic shift in what constitutes acceptable individual behavior. Can you imagine the ways in which white people who continue to favor or even ignore the effects of white supremacy—from covert preferences to overt acts of hate toward black and brown people—will be forced to examine their thoughts and actions, knowing that they are being monitored by other white people? Can you imagine how that self-reflection will become augmented as those who fail to guard against the effects of white supremacy begin to lose relationships with friends and family who are committed to allyship?

When I envision a United States where whiteness receives no meaningful preference and non-whiteness, no harm, it seems unrealistic—almost utopian. For many black and brown people, that’s the stuff of dreams. Sometimes, I have to remind and reassure myself that it’s actually possible.

But it is possible.

If the last few years have shown us anything, it’s that Americans of all backgrounds are capable of rallying together, holding one another accountable, and putting in the hard work required to achieve meaningful progress. Truly effective allyship, by its very nature, grows and expands its reach. Once a critical mass of white people show one another that they are committed to heeding Dr. King’s warning against complacency and maintenance of the status quo, achieving true racial equity will be positioned all the more closely within our grasp.

Thanks for reading,

Johnathan

Twitter/Facebook: @JohnathanPerk